Workshop Delved Into Present and Future of Quantum

At some point I realized, silicon photonics, and using light instead of electrons, actually is now not a science fiction thing.”

— Nikos Hardavellas

Professor of Computer Science and of Electrical and Computer Engineering

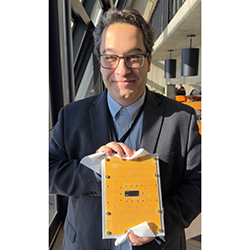

Nikos Hardavellas

Nikos Hardavellas

Key researcher’s work has advanced across generations of computers, leading to current quantum software stacks that were focus of recent NU event

Nikos Hardavellas, Northwestern professor of computer science and computer engineering and director of the Parallel Architecture Group (PARAG@N), has undertaken decades of research aimed moving onward and upward the performance of computer systems, helping lead to today’s intermediate-scale quantum computers.

On October 30, Hardavellas co-hosted with several other NU researchers part two of the Quantum System Software Stack (QS3) Workshop, an event co-sponsored by the university’s Initiative for Quantum Information Research and Engineering (INQUIRE) and the Northwestern + Argonne Institute for Scientific and Engineering Excellence (NAISE).

“The work that we do revolves around taking advantage of developments in new materials, new processes and new technologies to overcome bottlenecks, specifically [due to] the antiquated designs of computer systems,” taking them to greater scale with higher energy efficiency, he says.

“It was a privilege to welcome colleagues from academia and industry to Northwestern for the second QS3 workshop,” Hardavellas adds. “As the discussions unfolded, we saw the broad range of research touchpoints, and the key challenges we must address to advance this critical technology. We look forward to continuing the series as a platform that reinforces our collaborative ecosystem, sparks new connections, and lays the groundwork for future synergies and cross-cutting innovation across the full quantum stack, from devices and pulse engineering, to compilers and schedulers, to algorithm design for frontier scientific exploration.”

This research has continuously cannibalized itself over the decades because the pace of improvement has been so rapid, that what has seemed like science fiction in one decade becomes reality in the next, Hardavellas says.

“Suddenly, you realize that there’s all these problems that we couldn’t find good solutions for, that 10 to 12 years later, we have seen the light at the end of the tunnel,” he says. “At some point I realized, silicon photonics, and using light instead of electrons, actually is now not a science fiction thing. So we started working on chiplet-based systems that are connected through light to be able to improve performance, energy consumption and power consumption, and have great success with it.”

After Hardavellas built his early career at Northwestern on that topic, the previously esoteric, science-fiction-like curiosity of quantum computing reached a stage of usability by the late 2010s, in which users from the general public can log onto a quantum machine through the cloud. So he turned his attention toward the possibility of performance that exponentially surpassed classic computation, leading to the potential for everything from individualized pharmaceutical designs to more advanced metal alloys.

However, significant gaps remain between the computational needs of the algorithms that would produce these sorts of results and the currently available hardware, so Hardavellas and his colleagues have been working on the quantum system software infrastructure to help close that gap. “Current implementations are really constrained,” he says. “They have very few qubits [quantum bits], and we need a large number of qubits because that’s essential for algorithms with many variables.”

In addition, those qubits need to maintain very high coherence times for those algorithmic computations to be executed, Hardavellas says, and they need high gate fidelities for operations to be as accurate as possible. “And quantum hardware today is not there,” he says. “Quantum hardware needs to improve by several orders of magnitude, in all three of those dimensions—qubit scale, coherence times and gate fidelities—before it can become truly useful for a wide range of applications.”

While hardware is expected to bridge that gap, that’s probably a decade or more away—so for now, researchers are trying to complement existing hardware with a software stack that best leverages the available, limited, imperfect underlying hardware resources in the most efficient manner possible, Hardavellas says. “If part of your machine is much better than some other part of your machine, you direct your computation there,” he says. “We’re building software that does exactly these things,” automatically finding the best matches.

In doing so, the software simultaneously lowers the demands of the algorithms and elevates the capabilities of the hardware, Hardavellas says. “And now, the hardware has a much smaller gap to close with its development, as opposed to the huge gap that currently exists,” he says. “The compiler is the software that is tasked with mapping the algorithm to the hardware substate in the best way possible.”

Hardavellas has been collaborating for many years with Kate Smith, assistant professor of computer science, on this research, and the pair co-hosted the October 30 workshop along with three other faculty members. The first iteration of QS3, held in May, explored more generally the questions and challenges of developing a quantum software system stack. The more recent event, which opened Midwest Quantum Week, focused on compilation.

“The workshop looked at compilation in both this noisy, intermediate-scale quantum, which is what today’s systems are called,” ranging from a few hundred up to 1,000 qubits, imperfectly designed, he says. “But we also looked forward into what’s going to happen in the future. We expect to have what is called fault-tolerant quantum computing,” with improved computational quality.

The event also examined hybrid quantum-classical computing, in which classical systems, including graphics processing units (GPUs), supercomputers and others are bridged with quantum systems to solve problems together through compilers, rather than attempting to use one or the other, Hardavellas says.

“In this case, the compiler is going to make an ideal cut, let’s say, of the problem that you’re trying to solve, between the classical and the quantum domains,” he says. “Then offload the computation to those two parts, and let those two parts collaborate together to provide an optimal solution. The [event] covered this entire range. It was not only focused on what happens today, but also more so forward-looking.”

Cover photo by Edward Boe, Fermilab